From the liner notes by Bill Munson

One hit wonders are generally forgotten quickly, however unfair that fate may be. So it’s something of a tribute to the skill and spirit of Motherlode that people still get misty-eyed thinking about them a full quarter-century later. The highlight of the group’s short career was “When I Die”, an international hit that came out of nowhere in the middle of 1969. The hit justified a strong album, yielding two more failed singles, and the opportunity to record a second album. Unfortunately, the four guys in the original Motherlode parted company in January 1970, a little more than a year after it had all started.

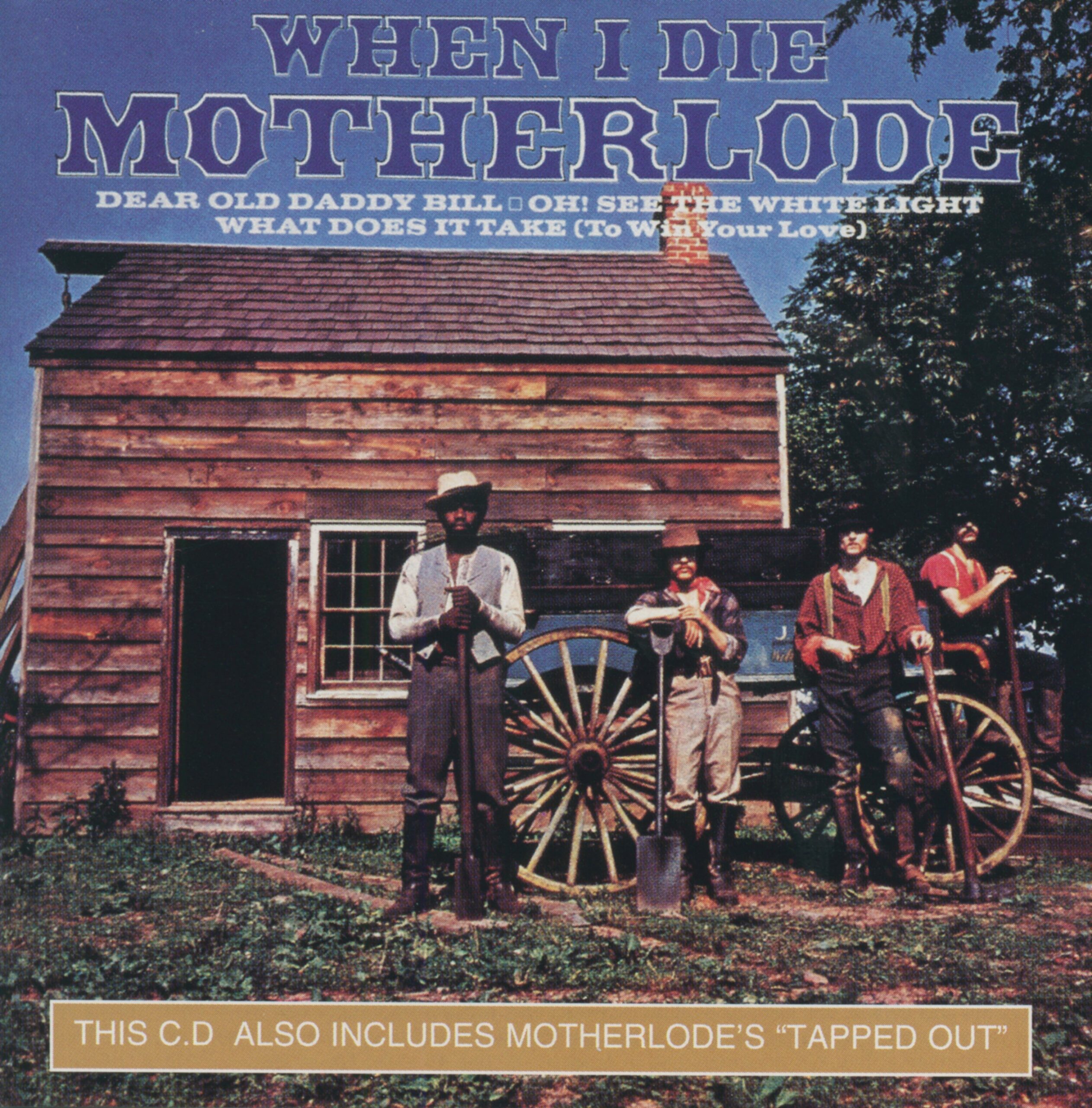

Although there were several later editions of the group, the most significant lineup consisted of organist William “Smitty” Smith, saxman Steve Kennedy, guitarist Ken Marco and drummer Wayne Stone. Their impressive technical capabilities, vocal and songwriting talents produced a big, rich sound full of sparkle and soul. It may, in fact, have been an embarrassment of riches that pulled the group apart, as all but Stone shared singing and writing duties.

Smitty and Kennedy had been playing together around Toronto for some time as members of the Soul Searchers, a four-piece band fronted by Eric Mercury and Diane Brooks — two superlative singers. With the demise of the Soul Searchers in 1968, first Kennedy, then Smitty, joined Grant Smith and the Power, a popular R&B band who’d had a big hit in 1967 with a dynamite version of “Keep On Running”. Wayne Stone had been with the Power for several months while Ken Marco joined at about the same time as Smitty.

Soon enough Smitty, Kennedy, Marco and Stone struck out on heir own, playing their first gig at the Image Club in London, Ontario. Within months they found themselves recording a couple of originals, including “When I Die”, for producers Mort Ross and Doug Riley. (Riley, Toronto’s R&B maestro, had played with Kennedy some years before in the Silhouettes and had known Smitty for ages.) “When I Die” was released as a single (on Ross’ Revolver Records in Canada and Buddah everywhere else) and became a huge international hit in the summer of 1969.

Oddly enough, hitting internationally turned out to be the easy part. Following up proved to be something else! The first attempt, “Memories Of A Broken Promise”, was released towards the end of 1969 while the band prepared to record a second album. It certainly sounded like the same group — that is, Smitty’s voice and organ playing stood out — but the single only managed to struggle onto the bottom rungs of the charts. (The song was written by former Soul Searcher Diane Brooks, who recorded her own album for Revolver which included one of their tunes, “The Boys Are On The Case”.)

Sessions for the second album were progesssing slowly due to conflicts within the band. While a couple of worthy successors to “When I Die” were eventually produced, Revolver was unable to wait. They reached back to the first album for the third single “Dear Old Daddy Bill”. With less of Smitty and more of the higher, thinner voices of Marco and Kennedy it was not what the fans wanted to hear.

The band broke up shortly after the completion of the brilliant second album. It appeared posthumously, but only in the US. The package included loving liner notes that expressed genuine dismay that Motherlode was no more. While it was true that the original Motherlode (Motherlode I) split up, Revolver Records owned the name and was still not prepared to let go of a good thing. Instead, they had Smitty replenish the ranks with three new musicians — drummer Philip Wilson, guitarist Anthony Shinault and sax player Doug Richardson. (Wilson, recognized in avant garde jazz circles, had just come off an extended stint with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, whose performance of Wilson’s “Love March” appears on the first Woodstock album just before Hendrix rips into “The Star Spangled Banner”.) Together they managed to produce just one 45 in the Fall of 1970 — Smitty’s “I’m So Glad You’re You (And Not Me)” backed with Shinault’s instrumental “Whipoorwill”. Despite being very much in the style of “When I Die”, it most definitely lacked the sparkle of the original band. The new record flopped and the group split almost immediately.

Mort Ross then commissioned Gord Waszek of Leigh Ashford (who were by now signed to Revolver) to write a suitable song in preparation for another Motherlode campaign. The anthemic result, “All That’s Necessary”, was then recorded by a studio group (Motherlode III) drawn mostly from the ranks of Leigh Ashford plus singer Breen Leboeuf (of Chimo, yet another Revolver act) and bassist Mike Levine (later of Triumph). For the flip side, Ross raided his Motherlode I tape library for the beautiful instrumental, “The Chant”, which had appeared on the posthumous album as “Hiro Smothek (The Chant)”.

In order to promote the new single, a ‘touring’ group (Motherlode IV) had been assembled: bassist Mike Levine, singer Wayne St. John (later of the THP Orchestra and the Domenic Troiano Band), guitarist Kieran Overs (later of Stringband, now a noted jazz bassist), and two former members of Leigh Ashford, — drummer Wally Cameron and organist Newton Garwood. As it turned out, “All That’s Necessary” didn’t sell well, despite good airplay and promotion, and there seemed little reason for the group to continue. Cameron and Garwood joined Waszek and Buzz Shearman in a new version of , and the othLeigh Ashforders moved on to various projects.

In March 1971, a Toronto newspaper featured a story on yet another Motherlode (Motherlode V): Dave Berman on sax, Brian Wray on keyboards, Joey Roberts (a.k.a. Miquelon) on guitar, Brian Dewhurst on drums and Gerry Legault on bass and vocals. This lineup was actually the remains of the Montreal-based Natural Gas, which had released an album on George Goldner’s Firebird label the previous year. No doubt finding life as Motherlode unfulfilling, the guys soon headed down the road as Truck, reclaiming their original powerhouse drummer, Graham Lear (later of Santana), along the way.

That was the last that anyone heard of Motherlode as a group for some time, although the original four guys certainly remained active on the music scene. Smitty became a much sought-after sideman in Toronto and Los Angeles, eventually settling in L.A. Among his many projects have been a number of albums with his old cohort Eric Mercury, one with Diane Brooks, and one under his own name. He and Marco were reunited in David Clayton Thomas’ first post-BS&T group (two albums with Clayton Thomas, plus another with Etta James), and Clayton Thomas used them both plus Steve Kennedy in the studio on other occasions. Kennedy himself became an enduring member of Doctor Music, a successful R&B/gospel/jazz group led by Doug Riley, while both Marco and Stone put in shorter stints with the same group.

In 1976 they all managed to get into the same studio at the same time to record Stone and Kennedy’s “Happy People”, a nice, swinging latin-flavoured number, along with three other tunes. Unhappily, they could not call themselves Motherlode and “Happy People” was released as by Kenny Marco alone. Too bad, as it deserved to be a hit and the Motherlode name would surely have given it extra cachet. The name did resurface in 1989, however, when the original quartet reunited for a week at the Club Bluenote in Toronto. They even managed to write and tape eight new songs the following year, but none have ever seen the light of day. Perhaps they eventually will!

Liner notes by Bill Munson with thanks to Steve Kennedy, Newton Garwood, Mark Miller and Mort Ross